Cardiac auscultation (listening to the heart) is one of the most commonly performed tasks by any veterinarian. When listening to the heart, the veterinarian is observing the heart rate, heart rhythm, and the heart sounds themselves. Most people think there are just two heart sounds, often described as ‘lub-dub’. However, there are actually four heart sounds, though not all of them can be heard in every horse. Each sound relates to a different event in the cardiac cycle. To understand what these sounds relate to, it is necessary to understand some anatomy of the heart.

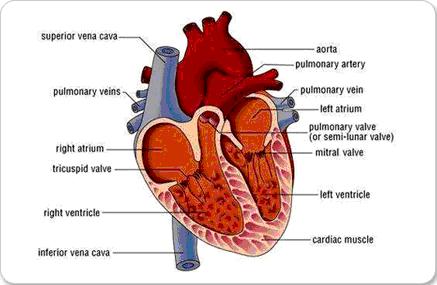

The heart consists of four chambers: two ventricles (left and right) and two atria (left and right). Veins supply blood to the heart and arteries carry blood away from the heart. Deoxygenated blood, which has been round the body and delivered the oxygen it was carrying to the organs and tissues, enters the right atrium through the cranial/superior and caudal/inferior vena cava (the major veins in the body). From here the blood enters the right ventricle. There is a valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle known as the tricuspid valve. When the heart beats, the blood is forced out of the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery, which carries the blood to the lungs to be oxygenated (saturated with oxygen). The newly oxygenated blood re-enters the heart, into the left atrium, via the pulmonary vein. The blood crosses the mitral valve to enter the left ventricle, from where it is carried via the aorta (major artery in the body) to the supply the rest of the body with oxygenated blood. There are two more valves in the heart, at the entrance to the pulmonary artery and the aorta, known as the pulmonic and aortic valves respectively. The function of valves is to prevent back-flow of blood into the area it has just been extracted from, when the pressure falls in the circulatory system at the end of the heart beat.

The heart consists of four chambers: two ventricles (left and right) and two atria (left and right). Veins supply blood to the heart and arteries carry blood away from the heart. Deoxygenated blood, which has been round the body and delivered the oxygen it was carrying to the organs and tissues, enters the right atrium through the cranial/superior and caudal/inferior vena cava (the major veins in the body). From here the blood enters the right ventricle. There is a valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle known as the tricuspid valve. When the heart beats, the blood is forced out of the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery, which carries the blood to the lungs to be oxygenated (saturated with oxygen). The newly oxygenated blood re-enters the heart, into the left atrium, via the pulmonary vein. The blood crosses the mitral valve to enter the left ventricle, from where it is carried via the aorta (major artery in the body) to the supply the rest of the body with oxygenated blood. There are two more valves in the heart, at the entrance to the pulmonary artery and the aorta, known as the pulmonic and aortic valves respectively. The function of valves is to prevent back-flow of blood into the area it has just been extracted from, when the pressure falls in the circulatory system at the end of the heart beat.

A stethoscope is used to auscultate the heart. The heart can be heard on both the left and right sides. The head of the stethoscope is placed on the chest wall, between the level of the point of the shoulder and the point of the elbow. To best hear the heart, it is necessary to place the stethoscope just under the triceps muscle mass. Some nervous horses object to the vet pushing these muscles out of the way, but the majority of horses tolerate it well. The right side of the heart can be more difficult to hear than the left; asking the horse to stand with the right leg forward can help the vet to hear the heart on the right.

A stethoscope is used to auscultate the heart. The heart can be heard on both the left and right sides. The head of the stethoscope is placed on the chest wall, between the level of the point of the shoulder and the point of the elbow. To best hear the heart, it is necessary to place the stethoscope just under the triceps muscle mass. Some nervous horses object to the vet pushing these muscles out of the way, but the majority of horses tolerate it well. The right side of the heart can be more difficult to hear than the left; asking the horse to stand with the right leg forward can help the vet to hear the heart on the right.

The cardiac cycle is divided into two phases: systole and diastole. Systole is the shorter phase of the cycle, when the ventricles contract to empty blood into the pulmonary artery and aorta, and is between ‘lub’ and ‘dub’, when listening to the heart. Diastole is the longer phase, when the ventricles are filling with blood ahead of the next heart beat, and is between ‘dub’ and the next ‘lub’. If you can feel the horse’s pulse at the same time, such as the facial artery where it curves around the mandible (bottom jaw), this will help you determine which phase is which; you should be able to feel the pulse during systole.

A cardiac murmur is defined as any sound that occurs between the normal heart sounds. Therefore, it is important to understand what the normal heart sounds are:

- S1 – Closure of the mitral and tricuspid valves (known as the atrioventricular valves or AV valves for short), which occurs at the start of systole when the ventricles contract to expel blood into the arteries. These valves close to stop blood flowing back into the atria.

- S2 – Closure of aortic and pulmonary valves (also known as the semilunar valves), which occurs at the end of systole when the ventricles stop contracting. These valves close to stop blood flowing back into the heart from the arteries.

- S3 – Passive filling of the ventricles with blood from the atria, which occurs early in diastole. The AV valves are open at this stage to allow this to occur.

- S4 – Contraction of the atria to actively fill the ventricles with blood.

S4 can be heard in most horses, and is heard just before S1, such that when auscultating the heart the heartbeat sounds like ‘le-lub dub’. S3 is heard just after S2, but is less audible and requires practice before it can be heard in most horses.

Not all murmurs are pathological (associated with heart disease), some are considered physiological (normal under the appropriate circumstances). In order to distinguish between a normal and an abnormal murmur, it is necessary to characterise the murmur. There are several categories used to describe murmurs, such as:

- Timing - the phase of the cardiac cycle in which the murmur occurs (i.e. systole or diastole)

- Duration - the period where the murmur is detected in the cycle (e.g. early during systole, mid-diastole, etc)

- Intensity – this is graded from 1 to 6 (see below)

- Quality – harsh, coarse, rumbling, scratchy, musical, honking, blowing

- Point of maximum intensity (PMI) – the point at which the murmur can be heard the clearest, often indicated by the rib space it is heard through and the side of the horse.

- Intensities of heart murmurs are graded as follows:

- Grade 1: very quiet, only audible after listening for several seconds

- Grade 2: quiet, requires careful auscultation to detect

- Grade 3: moderate, easily audible

- Grade 4: louder than the normal heart sounds

- Grade 5: loud, can be detected by feeling the chest wall (known as a precordial thrill)

- Grade 6: very loud, audible without actually placing the stethoscope on the body wall

As mentioned before, a cardiac murmur is any sound that occurs between the normal heart sounds, and is due to disruption of normal blood flow. A major cause of disrupted or turbulent blood flow in horses is due to leaky valves that allow blood to flow back into the chamber of the heart that it has just been extracted from by contraction of the chambers. These leaks are often small, so the blood that flows back does so at an accelerated speed, and this causes the audible murmur. Small animals and humans can have stenotic valves, which means that the valve opening is smaller than it should be, but this does not occur in horses. Horses can also have a ‘hole in the heart’, known as a ventricular septal defect, which causes a murmur due to blood flowing directly from one ventricle into the other through the hole. Another cause of murmurs, due to non-cardiac disease, is altered blood viscosity, as occurs with anaemia or low blood protein levels, and also in horses with endotoxaemia (toxins in the blood).

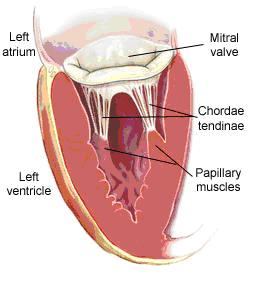

Valves can become leaky for a variety of reasons. The most common cause is degeneration of the valve leaflets with age. Instead of being thin flaps of tissue, the valves become thickened or develop nodules. When this occurs, they tend to shorten, so when the valve leaflets close, they do not come together properly and form a complete seal. Very rarely, horses are born with abnormally small valve leaflets; this is more common in humans and small animals. The valve leaflets can become infected and the resulting inflammation causes the valve leaflet to become deformed. Another, very serious cause of a leaky valve is rupture of the chordate tendinae, which are the cords that attach the valve leaflets to the wall of the ventricles. They are responsible for enabling the valve leaflets to close across the valve opening, without prolapsing into the atria, a little like tying a sail down so it doesn’t flap in the wind. If these chordate tendinae rupture, the valve leaflets cannot close across the valve opening, and the horse is in very serious trouble as the heart’s function is severely compromised. When this occurs the horse goes into acute, severe heart failure and almost inevitably dies.

Valves can become leaky for a variety of reasons. The most common cause is degeneration of the valve leaflets with age. Instead of being thin flaps of tissue, the valves become thickened or develop nodules. When this occurs, they tend to shorten, so when the valve leaflets close, they do not come together properly and form a complete seal. Very rarely, horses are born with abnormally small valve leaflets; this is more common in humans and small animals. The valve leaflets can become infected and the resulting inflammation causes the valve leaflet to become deformed. Another, very serious cause of a leaky valve is rupture of the chordate tendinae, which are the cords that attach the valve leaflets to the wall of the ventricles. They are responsible for enabling the valve leaflets to close across the valve opening, without prolapsing into the atria, a little like tying a sail down so it doesn’t flap in the wind. If these chordate tendinae rupture, the valve leaflets cannot close across the valve opening, and the horse is in very serious trouble as the heart’s function is severely compromised. When this occurs the horse goes into acute, severe heart failure and almost inevitably dies.

Horses are prone to physiological murmurs as they have such large hearts and large blood vessels, so some turbulent blood flow is not surprising. These murmurs are of no clinical significance. They are low intensity (grade 3/6 or less) and can be localised to specific valves. For example, if the murmur occurs during systole, it is localised over the aortic or pulmonic valves and reflects turbulent blood flow in the aorta or pulmonary artery as the blood is being ejected from the ventricles into these vessels. If it occurs in diastole, it can be localised over the mitral or tricuspid valve, reflecting turbulent blood flow through these valves from the atria into the ventricles during diastole. If it occurs on the left, it is associated with the mitral valve, and if it is heard on the right, it is the tricuspid valve. Pathologic murmurs, associated with heart disease, are often of longer duration, greater intensity (greater than grade 3/6) and sound very course. These murmurs are candidates for further investigation.

The particular valve or lesion causing the murmur can be strongly suspected from very thorough cardiac auscultation. The vet recognises that a murmur is present and grades it. If the murmur is severe, the vet will recommend further investigation. This requires an echocardiogram, or ultrasound of the heart. This is an extremely specialised technique, which only a select few equine veterinarians in the country are qualified to perform, and a referral is required from your vet to the specialist. In the meantime, whilst waiting for the appointment with the specialist, your vet is likely to advise that you do not ride your horse until given the ok by the specialist, as some horses are at risk of collapse during exercise due to the nature of their heart disease.

The echocardiogram enables the exact nature of the lesion causing the murmur to be identified. This may be a leaky valve, or a ventricular septal defect (VSD), or some other lesion. During an echocardiogram, the veterinarian will use colour flow Doppler ultrasound to detect the area of abnormal blood flow. Doppler ultrasound detects blood flow towards and away from the transducer (probe), seen as shades of red and blue respectively. When there is turbulent blood flow, such as through a leaky valve, blood flows in all different directions, causing a ‘flash’ of white, yellow and light blue. The width and length of this jet of turbulent blood flow indicates the degree to which the valve is leaking and the severity. During the echocardiogram, the veterinarian will also measure the size of the chambers of the heart and the contractility of the heart. All of these factors combined indicate the severity of the lesion and the likely effect it will have on the horse. The examination will also provide a baseline; the veterinarian may recommend a repeat examination in 6-12 months to note any progress of disease. Some lesions remain static for a number of years, and the horse can go on to work for several more years with no problems. However, if the lesion appears to be progressing, it may be advisable to retire the horse. In such cases the horse is at risk of collapsing, particularly during exercise, and this could endanger the rider. If the horse is a mare, some people retire them to be brood mares and, unless the cardiac disease is very severe, these mares can often successfully breed with a heart murmur.

The echocardiogram enables the exact nature of the lesion causing the murmur to be identified. This may be a leaky valve, or a ventricular septal defect (VSD), or some other lesion. During an echocardiogram, the veterinarian will use colour flow Doppler ultrasound to detect the area of abnormal blood flow. Doppler ultrasound detects blood flow towards and away from the transducer (probe), seen as shades of red and blue respectively. When there is turbulent blood flow, such as through a leaky valve, blood flows in all different directions, causing a ‘flash’ of white, yellow and light blue. The width and length of this jet of turbulent blood flow indicates the degree to which the valve is leaking and the severity. During the echocardiogram, the veterinarian will also measure the size of the chambers of the heart and the contractility of the heart. All of these factors combined indicate the severity of the lesion and the likely effect it will have on the horse. The examination will also provide a baseline; the veterinarian may recommend a repeat examination in 6-12 months to note any progress of disease. Some lesions remain static for a number of years, and the horse can go on to work for several more years with no problems. However, if the lesion appears to be progressing, it may be advisable to retire the horse. In such cases the horse is at risk of collapsing, particularly during exercise, and this could endanger the rider. If the horse is a mare, some people retire them to be brood mares and, unless the cardiac disease is very severe, these mares can often successfully breed with a heart murmur.

A very loud murmur does not necessarily equate to a severe lesion. For example, murmurs associated with VSDs reflect the flow of blood through the hole in the septum between the left and right ventricles. If the hole is very large, blood will flow at a slower rate through the hole as it is under less pressure, and the resulting murmur is usually quieter than flow through a small hole. This is because, if the hole is small, the blood is forced through that hole under higher pressure and travels at a greater velocity, which causes more turbulence creating a greater intensity murmur. However, the amount of blood that crosses through the hole is much smaller if the hole is small, and this is much less serious than if a larger amount of blood goes the wrong way through a large hole. Thus, the lesion is not considered particularly severe, yet the murmur sounds very severe. Think of what happens when you place your thumb over the end of a hosepipe. Therefore, it is worth having an echocardiogram performed on your horse’s heart, to fully characterise the nature and severity of the lesion, before condemning the horse based on auscultation of the heart alone.

The circulatory system is responsible for delivering oxygen, nutrients and other important factors to the various tissues in the body, via the blood. For this system to work effectively, it must be a closed system where flow occurs in one direction only. When there is a leaky valve, for example, less blood is pumped out of the ventricles into the arteries to go round the body with each heart beat, as some of the blood flows back into the atria. Thus, the heart may only be working at 85% efficiency. At rest or in the paddock, this is unlikely to have any effect on the horse. However, if the horse performs endurance, or is a racehorse, for example, this degree of inefficiency in the system can have a serious effect on the horse, as oxygen is not being delivered to the tissues effectively and not meeting their oxygen demands. Such horses cannot cope with the level of exercise asked of them, and are exercise intolerant. This is why heart murmurs are so important. Other horses have such advanced cardiac disease that they are affected at rest. For example, some horses lose weight or fail to put on weight. The disease can progress and cause the horse to go into heart failure, but most horses do not progress this far.

Having said all of the above, much research has been conducted into the frequency of heart murmurs amongst horses, particularly racehorses and these studies have found that heart murmurs are a common finding among racehorses, and most do not seem to be clinically significant. Thus, if your vet mentions that your horse has a heart murmur, it is not necessarily the end of your horse’s career. The vet will fully assess the horse’s cardiovascular system, and consider what the horse is used for. With a more complete picture of the situation, the vet will decide if it is necessary to further investigate the murmur, or if the murmur is likely to be of no clinical significance. From personal observations, it is not uncommon to come across a horse with a heart murmur, but very few are serious enough for me to recommend further investigation.